Overview

Named after the Virgin Mary of the Assumption, the Orvieto Cathedral represents one of the artistic masterpieces of the late Italian Middle Ages, which gathered under one roof the feeling that pervaded the construction of the great European Cathedrals of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The Orvieto Cathedral – Duomo

The Orvieto cathedral is so famous worldwide that a large number of people come to the “City of the Cliff” attracted only by its great iconic monument. However, Orvieto’s Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption (to the Orvietani, but not only, simply the Duomo) is undoubtedly the town’s most important and unrivalled wonder.

Celebrated over the centuries by artists and writers as well as by ordinary people, the Orvieto cathedral will never cease to amaze you, no matter how well informed you are, how much you have read about it or how many pictures or postcards you have enjoyed seeing.

Coming to Orvieto and having the best stay:

- Compare prices of hotels near the Orvieto cathedral, for all pockets or view hotel deals at the bottom of the page that we have for you.

- Find cheap flights to Orvieto.

- Here is a selection of Travel guides for Orvieto

and its Cathedral

.

- And something else for you, selection of:

Guides and tours in Orvieto:

See our Top 15 catholic shrines around the world.

See more Italian Catholic shrines and Basilicas

See more European Catholic Shrines and pilgrimages

Whichever direction you are coming from, you will be amazed at its daring and slender proportions, surely a hymn to the desire for infinity and ascent to heaven – and its unique impressiveness and evocativeness, that go beyond any simplistic categorization of style.

Named after the Virgin Mary of the Assumption, the Orvieto cathedral represents one of the artistic masterpieces of the late Italian Middle Ages, which gathered under one roof the feeling that pervaded the construction of the great European Cathedrals of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The architectural solutions of the mendicant orders and the figurative motifs of the French Gothic art, in order to overcome the tradition followed by Roman basilicas and create an ensemble which would be unrepeatable and totally original.

Built over the course of several centuries (from the thirteenth to the seventeenth) with additions dating back even to the more modern twentieth century, the vast ensemble of the Cathedral of the Virgin Mary of the Assumption owes its construction to a multitude of reasons.

Certainly religious, as tradition has it, due to the close link between the Duomo and the 1263 Miracle of Bolsena, but also, more widely, political, social, and artistic reasons as well as those related to town planning.

The Orvieto cathedral and the Miracle of Bolsena

As it is usually narrated, the Orvieto Cathedral was built in order to celebrate a fundamental event for the Christian world: the 1263 Miracle of Bolsena. As narrated by a sacred representation dating back to the first half of the fourteenth century and the subsequent popular tradition, a Bohemian priest, tormented by the doubt whether the consecrated host was Christ’s body and blood, went on a pilgrimage to Rome in 1263 to strengthen his faith.

On his way back he stopped in Bolsena to celebrate mass at the altar of Saint Christina’s Basilica; at the moment of consecration he saw the broken host spill some stills of blood, that stained the Corporal, a linen cloth used during the functions.

Once Pope Urban IV, who had been residing in Orvieto since 1262, learnt about the miracle, he sent the town’s Bishop to Bolsena so that the latter would take the relic represented by the sacred linen cloth to the Church of Saint Mary; the Pontiff himself waited by the Rio Chiaro bridge for the relic to arrive and a solemn procession accompanied it to its final destination.

The Orvietani thought the existing cathedral appeared too modest to host such a precious relic, therefore they decided a new religious building should be constructed, splendid and magnificent enough to match such a great miracle.

Besides this tradition, it is a proven fact that the old Church of Saint Mary Prisca was in such a bad condition that the most important ceremonies needed to be held in other places of worship; also, Pope Urban IV had issued the “Transiturus de hoc mundo” Papal Bull on 11 August 1264 which established and extended the Corpus Domini festivity to the whole Catholic world, with the underlying purpose to create a front against a multitude of heresies.

Orvieto was experiencing a flourishing civil and economic development at the time, together with a great religious fever, to which the Miracle of Bolsena and the Transiturus Bull had certainly contributed.

Therefore there was a general need for a new cathedral, and Francesco Monaldeschi, who served as Orvieto’s Bishop between 1279 and 1295, took this responsibility upon himself: meeting a general wish, he envisaged the construction of an imposing and beautiful building, that required the demolition of the Church of Saint Mary and the Parish Church of Saint Constant.

The Orvieto cathedral interior

The richness and the complex and articulated decoration of the façade of the Orvieto Cathedral find their counterpoint in the sober and bare atmosphere enveloping visitors at the entrance: you will surely feel its wave of engaging and serene vastness.

Articulated in three naves separated by ten cylindrical columns and two octagonal pillars, the interior is held together by six large bays and, through wide and slender semi circular arches, it expands sideways into the external naves that are totally visible and serve as a background to the central area.

The impression of aerial lightness is made more evident by the sequence of the semi-cylindrical chapels and of the mullions located on the perimeter walls, that create an effect of spatial deepening, while the painted roof truss in the front section of the building enhances the concentrated aura of silence and mysticism with an indefinite half-light.

The continuous transept, with three cross vaults of the same height, which is completely independent from the longitudinal body and is contained in the rectangle of the naves, to create a shadowy background before the square-shaped tribuna, is a completely original solution.

In the apse area a vast cycle of paintings can be admired, that includes the Stories of the Virgin Mary, commissioned in 1370 to local painter and mosaicist Ugolino di Prete Ilario, who had already distinguished himself for realizing the paintings of the Corporal Chapel together with Friar Giovanni di Leonardello between 1357 and 1364.

The paintings required repair in order to be preserved during the following century to which Giacomo da Bologna (1491-94), Pinturicchio (1492) and Pastura (1497-99) contributed. The frescoes of the tribuna which had been covered with dust for a long time, underwent frequent interventions in the nineteenth century, that ended with the last and important restoration of the 1990s.

Take a moment to observe the marble group of the Piety by Ippolito Scalza, located in the tribuna, on the left arm of the crossing. Conceived as early as 1550, this artwork was commissioned by the Fabbriceria del Duomo only in 1570 and completed by the artist in 1579, who carved it out of a single block of marble.

With dramatic effectiveness and through the four figures emerging from the marble, Scalza thinks deeply about the death of Jesus Christ, materializing his thoughts in the feelings of devastation appearing on the sculptured faces and in the strong gestural expressiveness.

The lifeless body of the Saviour is held by the Virgin Mary who, turning her torso and tragically lifting her left arm, takes her son into her bosom. Mary Magdalene, kneeling and crying, lays her face on Jesus Christ’s hand and holds his foot at the same time while Nicodemus, his forehead frowning in pain, watches the women crying holding nails and tongs in one hand, and a ladder and a hammer in the other, all elements clearly symbolizing Crucifixion and Deposition.

The two chapels on the Duomo’s sides, that is the Corporal Chapel and Saint Brizio’s Chapel, are worth stopping by for a calm and well-informed visit.

Conceived in order to preserve the memory of the Eucharistic Miracle of Bolsena (1263) forever and worthily host the Sacred Linen Cloth, the Corporal Chapel was built on the northern head of the transept between 1350 and 1356 and local Master Painter Ugolino di Prete Ilario was later entrusted with the task of painting and decorating it.

The cycle of paintings began from the vaults, possibly inspired by the enamels of the precious Reliquary the Corporal had been kept in since 1338.

As Ugolino himself pointed out in the autographed inscription located on the wall behind the altar, works terminated on 8 June 1364. Amongst the frescoes, the so-called Madonna of the Recommended stands out, made by Sienese Lippo Menni around 1320.

The Corporal Chapel too underwent renovation and modifications over the centuries, particularly during the Baroque and Mannerism periods. The Sepolcro di Orsino e Rodolfo Marsciano, attributed to Sanmicheli and Montelupo, was installed on the right wall in 1561;

Ippolito Scalza sculpted the Tomba del vescovo Sebastiano Vanzi (tomb of bishop Sebastiano Vanzi) in 1571; the red marble tiles describing the Miracle of Bolsena, located on the right wall were also made by Scalza in the sixteenth century.

The statues of two archangels made by Agostino Cornacchini were added to the sides of the altar in 1729. According to some local historians, it was during the second half of the nineteenth century that the most invasive interventions took place, such as the restoration of the paintings that, Luigi Fumi thought “took away the Chapel’s own character”; such interventions were carried out by painters Antonio Bianchini and Luigi Lais, who Pope Pius IX had directly entrusted with the task to recover the fourteenth-century frescoes that had particularly deteriorated.

Such alterations to Ugolino’s frescoes brought complaints from many art historians, but the restoration that took place in 1975-78, which led to the discovery of the underpaintings, confirmed that the nineteenth century interventions had not been as invasive as people had thought.

View hotel deals in Orvieto:

Let us remain close in the same prayer! May the Lord bless you abundantly!

Special Offer

The Duomo and the Miracle of Bolsena

As it is usually narrated, Orvieto Cathedral was built in order to celebrate a fundamental event for the Christian world: the 1263 Miracle of Bolsena. As narrated by a sacred representation dating back to the first half of the fourteenth century and the subsequent popular tradition, a Bohemian priest, tormented by the doubt whether the consecrated host was Christ’s body and blood, went on a pilgrimage to Rome in 1263 to strengthen his faith. On his way back he stopped in Bolsena to celebrate mass at the altar of Saint Christina’s Basilica; at the moment of consecration he saw the broken host spill some stills of blood, that stained the Corporal, a linen cloth used during the functions.

Once Pope Urban IV, who had been residing in Orvieto since 1262, learnt about the miracle, he sent the town’s Bishop to Bolsena so that the latter would take the relic represented by the sacred linen cloth to the Church of Saint Mary; the Pontiff himself waited by the Rio Chiaro bridge for the relic to arrive and a solemn procession accompanied it to its final destination. The Orvietani thought the existing cathedral appeared too modest to host such a precious relic, therefore they decided a new religious building should be constructed, splendid and magnificent enough to match such a great miracle.

Besides this tradition, it is a proven fact that the old Church of Saint Mary Prisca was in such a bad condition that the most important ceremonies needed to be held in other places of worship; also, Pope Urban IV had issued the “Transiturus de hoc mundo” Papal Bull on 11 August 1264 which established and extended the Corpus Domini festivity to the whole Catholic world, with the underlying purpose to create a front against a multitude of heresies. Orvieto was experiencing a flourishing civil and economic development at the time, together with a great religious fever, to which the Miracle of Bolsena and the Transiturus Bull had certainly contributed. Therefore there was a general need for a new cathedral, and Francesco Monaldeschi, who served as Orvieto’s Bishop between 1279 and 1295, took this responsibility upon himself: meeting a general wish, he envisaged the construction of an imposing and beautiful building, that required the demolition of the Church of Saint Mary and the Parish Church of Saint Constant.

In any case, even if legend more than real history, the traditional link between the Duomo and the Miracle of Bolsena has always been alive in the devotion of the locals; historians and scholars, such as Luigi Fumi, just to name one, have been aware of it too. Finally, Pope John Paul II, in the homily pronounced from Orvieto’s Duomo on 17 June 1990, during the Corpus Domini celebrations, tried to clarify this matter, by stating: “even though the construction [of the Duomo] is neither directly connected to the solemnity of the Corpus Domini, established by Pope Urban IV in 1264 with the Transiturus Bull, nor to the miracle that had taken place in Bolsena the previous year, with no doubt the Eucharistic Mystery is here powerfully evoked by the Bolsena Corporal, for which the chapel that enshrines it now was purposely built”.

Let us remain close in the same prayer! May the Lord bless you abundantly!

Video

Let us remain close in the same prayer! May the Lord bless you abundantly!

Let us remain close in the same prayer! May the Lord bless you abundantly!

Weekday – November to February:

- 9.00 – Chapel of the Sacred Corporal

Sundays and Celebrations – November to February:

- 9:00

- 11:30

- 17:00

Weekday – March to October:

- 9.00 – Chapel of the Sacred Corporal

Sundays and Celebrations – March to October:

- 9:00

- 11:30

- 18:00

Let us remain close in the same prayer! May the Lord bless you abundantly!

Let us remain close in the same prayer! May the Lord bless you abundantly!

Let us remain close in the same prayer! May the Lord bless you abundantly!

Let us remain close in the same prayer! May the Lord bless you abundantly!

Let us remain close in the same prayer! May the Lord bless you abundantly!

The Façade

If you wish to fully enjoy the wonderful façade of Orvieto Cathedral, we suggest you sit peacefully on the ancient stone benches at the feet of the palaces that face the cathedral from across the square. First of all, let an overall impression go right through you, simply and spontaneously, and then start considering the architectural elements and the vast iconography, greatly expressed by the bas-reliefs and the decorating sculptures and mosaics.

Built on the basis of a drawing showing three-pinnacles, which is now kept in the Opera del Duomo archives, the façade looks like a three-part wall, where a geometric motif is repeated three times: a door framed by pillars and surmounted first by a pediment and a loggia, and then, at the top, by a pinnacle, while the large rose window by Orcagna lays in the centre inside a square frame.

Up to the loggiato, the front of the Orvieto Cathedral is strongly characterized by medieval artistic concepts; its realization probably dates back to the late thirteenth century and first ten years of the fourteenth century. The construction of the facade started under the supervision of an unknown Master Builder, possibly at the same time as the main body of the building, and was carried on by Lorenzo Maitani, who, by introducing stylistic methods belonging to the gothicism, broke the decorative unity between the facade and sides of the building and modified the previous project that required only one pinnacle.

After the death of Maitani, (1530) works went on rather slowly. After the rose window was completed (1354-1380), the side niches surrounding it were constructed as well as the minor pinnacles (1373-85).

On the other hand, the higher part was influenced by the fifteen and sixteenth century styles: the edicolae with the statues above the rose window were added (1451-55) and the small taberrnacles were inserted in the side spires in those ages. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Michele Sanmicheli started constructing the central pinnacle and the related spires: the top-left one, completed by Ippolito Scalza in 1569, and the top right one, completed by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger in 1543. Ippolito Scalza completed the facade with the construction of the last spires (1571-91).

After enjoying such an overall impression, you can observe in detail the bas-reliefs and the mosaics that in the artistic environments of those times, identified the originality of the Duomo’s façade decoration.

The bas-reliefs of the sculptural programme illustrated at the base of the four pillars of the facade describe stories from the Old and the New Testament. The scenes, sculpted on different wall sections which are separated by branches of acanthus, ivy and grapes, illustrate the History of Mankind from its origins to end of the world, with refined narrative skills and a definite eschatological purpose. The Incarnation and life of Jesus Christ play a fundamental role, and particular attention is paid to the themes of Redemption and Universal Judgement. The Virgin Mary, advocate of mankind and provider of salvation, is the bridge between the Old and the New Testament.

The first pillar illustrates stories from the Genesis: going from bottom to top and from left to right, the first section shows the first five days of creation, the second showing the sixth day; you will notice that there is no representation of God resting on the seventh day. These stories are followed by Life in Eden, the Original Sin, where it is unusually suggested that figs are the forbidden fruit, and the representation of people from the cursed line of Cain, practising the arts of trivium and quadrivium

The Jesse Tree appears on the second pillar, to represent the genealogy of Jesus Christ. The kings of David’s line are represented in the central trunk of the family tree, between Jesse sleeping at the bottom and Jesus Christ at the top; twenty-four prophets and as many ancestors of Jesus Christ are represented vertically along the sides of the pillar.

By narrating Stories from the New Testament, the third pillar confirms what had been prophesied on the second. Prophets or figures from the Books of the Prophets are sculptured symmetrically to the figure of Jesse near an old man sleeping and, starting from the third section, a sequence of scenes from the life of Jesus Christ are represented, from the Annunciation to the Noli me tangere.

In the fourth and last pillar an apocalyptic vision of the Universal Judgement is sculptured, that includes the Resurrection and the division between the Reprobate, condemned to the fire of Hell and the Elect, on their way to Heaven, preceded by a procession of Saints, men and women. And tradition has it that Lorenzo Maitani himself can be recognized amongst the Saints of the fourth section, as the figure carrying a square on his shoulder.

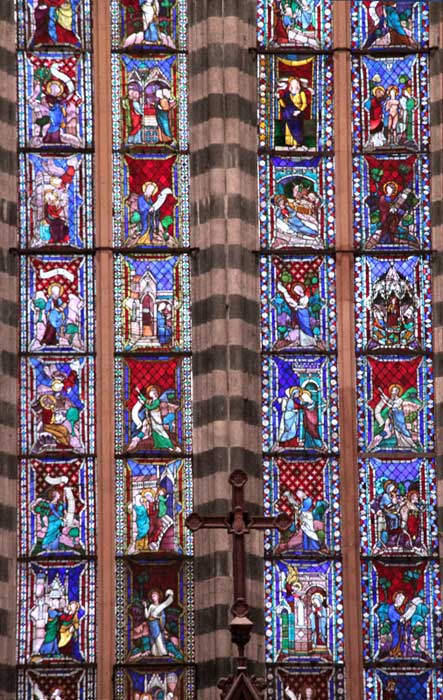

Above the bas-relieved base, enhanced by the white marble background, the mosaic decoration of the Duomo enriches a vast area of the facade surface with a lively polychromy, contributing an abundance of gold and other colours to the great suggestiveness of the overall vision. Particularly magnificent in the afternoon, when the sun light enhances its harmonious brilliance, it will however amaze you at any time and under any weather conditions for the richness and the beauty of its decorative patterns. Possibly taking inspiration from the culture of Paleo-Christian Rome, mosaic decorations were used on a golden background, a completely original choice in the artistic panorama of fourteenth century Italy, something that contributed to the uniqueness of Orvieto’s Duomo. Perfectly in line with the iconographic canon, in a Cathedral named after the Virgin Mary, the mosaics represent the highlights of the life of Mary, and reach their peak with the Coronation in the central tympanum; the only exception in this Marian cycle being the Baptism of Jesus Christ, represented above the left door.

For the realization of such a major mosaic project, that started in 1321 and went on until the sixteenth century, the Opera del Duomo promoted the local production of glass by having a glass furnace built for the work site; tesserae coming from the castle workshops of Monteleone and Piegaro were also used, as well as sheets of gold and silver leafs from Spoleto, and glass tesserae from Rome and Florence.

Many master glassmakers, painters and mosaicists were involved in this venture: Lorenzo Maitani, under whose direction the tower mosaic decorations, the bands and the frames were made, Giovanni di Bonino, who worked on the tribuna glass window, and Orcagna, who realized the Baptism of Jesus Christ between 1359 and 1360. Friar Giovanni di Leonardello and painter Ugolino di Prete Ilario the author of the drawings, the latter from Orvieto, created the mosaics of the Annunciation and the Nativity, while Cesare Nebbia worked on the Coronation on the main frontispiece in the sixteenth century. Many mosaic scenes underwent renovation at a later stage, which altered the original shape of decorations, or were replaced by new mosaics in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A curious event, albeit not a usual one, occurred upon the celebration of the Duomo’s fifth centenary (1790) when some of the original mosaics were detached and given to Pope Pius VI: the only mosaic scene out of those which has not been lost is the Nativity of Mary, which has been kept in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum since 1891.

The portals and doors definitely contribute to the majestic effect offered by the facade, particularly the superb central semicircular opening surmounted by the sculptured marble group of the Majesty with a baldaquin and bronze angels in the lunette (a copy of the original work which is kept in the near Papal palaces). The bronze statues of the four evangelists located on the frame surmounting the doors, and the side pillars, simply and daringly shining out, are extremely evocative.

The bronze doors currently installed, which replaced the ancient wooden doors in 1970, were made by Sicilian sculptor Emilio Greco (1964). Two large tri-dimensional angels are represented on the side doors while the theme of the Works of Mercy is developed over the six panels of the central door. The so called bishopric-door on the south side of the Cathedral deserves to be admired too, a fine work by Rubeus confirming the presence of Northern-European workforce during the first stage of the Cathedral construction.

The Duomo’s interior

The richness and the complex and articulated decoration of the façade of the Orvieto Cathedral find their counterpoint in the sober and bare atmosphere enveloping visitors at the entrance: you will surely feel its wave of engaging and serene vastness. Articulated in three naves separated by ten cylindrical columns and two octagonal pillars, the interior is held together by six large bays and, through wide and slender semi circular arches, it expands sideways into the external naves that are totally visible and serve as a background to the central area. The impression of aerial lightness is made more evident by the sequence of the semi-cylindrical chapels and of the mullions located on the perimeter walls, that create an effect of spatial deepening, while the painted roof truss in the front section of the building enhances the concentrated aura of silence and mysticism with an indefinite half-light. The continuous transept, with three cross vaults of the same height, which is completely independent from the longitudinal body and is contained in the rectangle of the naves, to create a shadowy background before the square-shaped tribuna, is a completely original solution.

In the apse area a vast cycle of paintings can be admired, that includes the Stories of the Virgin Mary, commissioned in 1370 to local painter and mosaicist Ugolino di Prete Ilario, who had already distinguished himself for realizing the paintings of the Corporal Chapel together with Friar Giovanni di Leonardello between 1357 and 1364. The paintings required repair in order to be preserved during the following century to which Giacomo da Bologna (1491-94), Pinturicchio (1492) and Pastura (1497-99) contributed. The frescoes of the tribuna which had been covered with dust for a long time, underwent frequent interventions in the nineteenth century, that ended with the last and important restoration of the 1990s.

Take a moment to observe the marble group of the Piety by Ippolito Scalza, located in the tribuna, on the left arm of the crossing. Conceived as early as 1550, this artwork was commissioned by the Fabbriceria del Duomo only in 1570 and completed by the artist in 1579, who carved it out of a single block of marble. With dramatic effectiveness and through the four figures emerging from the marble, Scalza thinks deeply about the death of Jesus Christ, materializing his thoughts in the feelings of devastation appearing on the sculptured faces and in the strong gestural expressiveness. The lifeless body of the Saviour is held by the Virgin Mary who, turning her torso and tragically lifting her left arm, takes her son into her bosom. Mary Magdalene, kneeling and crying, lays her face on Jesus Christ’s hand and holds his foot at the same time while Nicodemus, his forehead frowning in pain, watches the women crying holding nails and tongs in one hand, and a ladder and a hammer in the other, all elements clearly symbolizing Crucifixion and Deposition.

The two chapels on the Duomo’s sides, that is the Corporal Chapel and Saint Brizio’s Chapel, are worth stopping by for a calm and well-informed visit.

Conceived in order to preserve the memory of the Eucharistic Miracle of Bolsena (1263) forever and worthily host the Sacred Linen Cloth, the Corporal Chapel was built on the northern head of the transept between 1350 and 1356 and local Master Painter Ugolino di Prete Ilario was later entrusted with the task of painting and decorating it. The cycle of paintings began from the vaults, possibly inspired by the enamels of the precious Reliquary the Corporal had been kept in since 1338. As Ugolino himself pointed out in the autographed inscription located on the wall behind the altar, works terminated on 8 June 1364. Amongst the frescoes, the so-called Madonna of the Recommended stands out, made by Sienese Lippo Menni around 1320.

The Corporal Chapel too underwent renovation and modifications over the centuries, particularly during the Baroque and Mannerism periods. The Sepolcro di Orsino e Rodolfo Marsciano, attributed to Sanmicheli and Montelupo, was installed on the right wall in 1561; Ippolito Scalza sculpted the Tomba del vescovo Sebastiano Vanzi (tomb of bishop Sebastiano Vanzi) in 1571; the red marble tiles describing the Miracle of Bolsena, located on the right wall were also made by Scalza in the sixteenth century. The statues of two archangels made by Agostino Cornacchini were added to the sides of the altar in 1729. According to some local historians, it was during the second half of the nineteenth century that the most invasive interventions took place, such as the restoration of the paintings that, Luigi Fumi thought “took away the Chapel’s own character”; such interventions were carried out by painters Antonio Bianchini and Luigi Lais, who Pope Pius IX had directly entrusted with the task to recover the fourteenth-century frescoes that had particularly deteriorated.Such alterations to Ugolino’s frescoes brought complaints from many art historians, but the restoration that took place in 1975-78, which led to the discovery of the underpaintings, confirmed that the nineteenth century interventions had not been as invasive as people had thought.